CVE-2026-24834: When Trusting The Guest Goes Wrong

How a 9.4 CVE in Kata Containers reveals the most important design decision in microVM isolation

There's a question that sits underneath every microVM architecture, that most people never ask:

Do you trust the guest?

Not "do you trust the container," because everyone agrees containers aren't a security boundary. The entire point of microVM isolation is that you stop trusting the container and put a hypervisor between the container and everything else. Everyone has converged on this answer.

The harder question in microVM isolation architecture is what happens inside the VM. The guest kernel, the agent process, the mechanisms that make containers do container things inside a microVM. Do you fundamentally trust those?

This week, CVE-2026-24834 answered that question for Kata Containers. The answer was: yes, they trusted the guest. And the guest let them down.

What Happened in CVE-2026-24834?

The vulnerability is elegant: a container user, not even a privileged one, just a process with CAP_MKNOD, can overwrite arbitrary binaries on the guest VM's root filesystem and achieve code execution as root inside the microVM. CVSS 9.4. The attack requires no special tooling, no kernel exploits, no race conditions. Just mknod, debugfs, and an understanding of how the guest image is served.

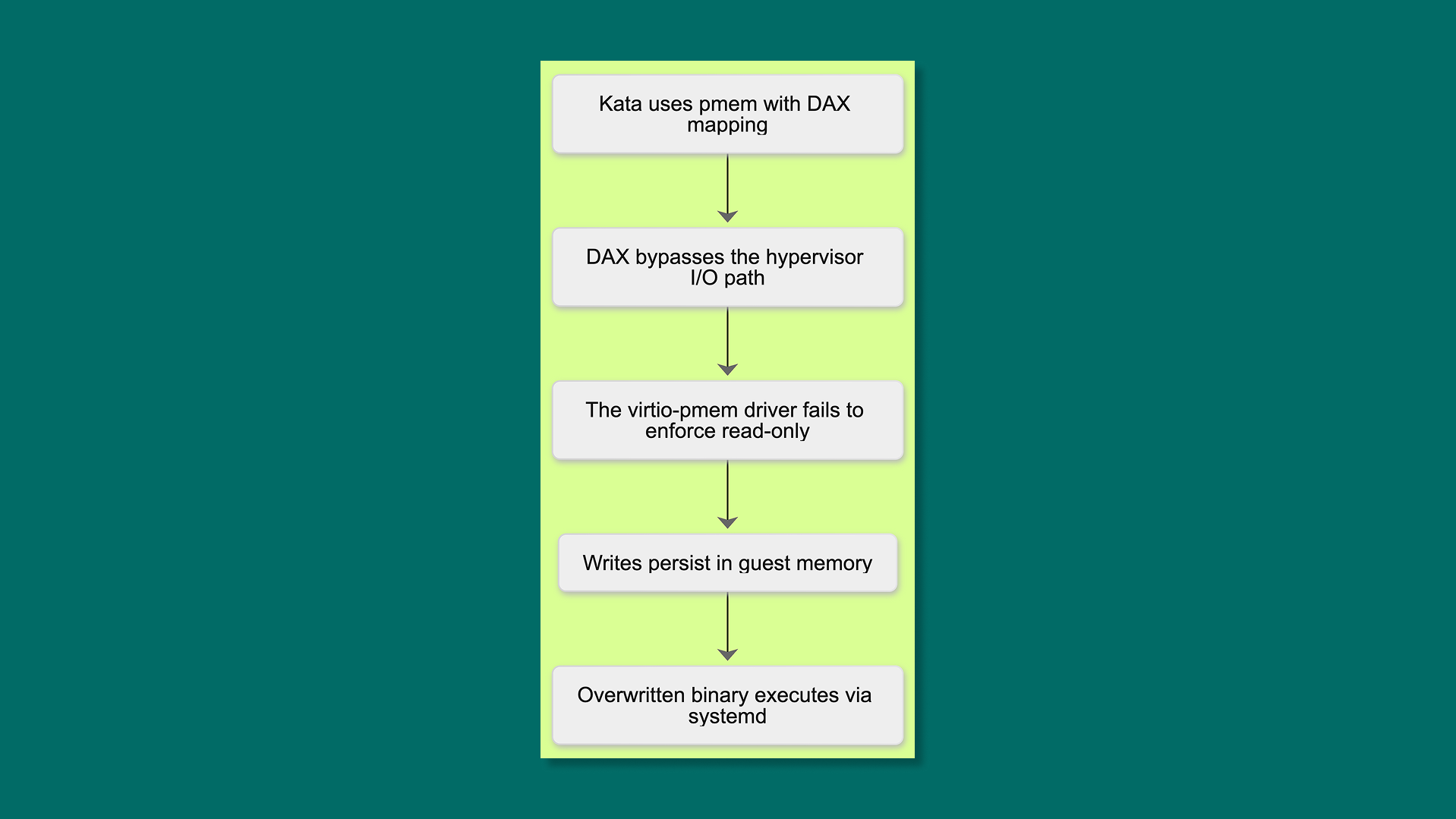

Kata uses persistent memory (pmem) with DAX mapping to serve guest image content. DAX is fast, it maps storage directly into the guest's address space, bypassing the hypervisor entirely. That bypass is the performance feature. It's also the vulnerability.

The Linux virtio-pmem driver never sets the read-only flag on the memory region. Cloud Hypervisor opens the backing file read-only and uses MAP_PRIVATE, so writes don't persist to disk. But writes do persist in memory. And because DAX maps the backing store directly into the guest, there's no path for the hypervisor to intercept. The guest kernel was supposed to enforce read-only semantics. It didn't.

An attacker creates the pmem block device, calculates the byte offset of a target binary, overwrites it with a reverse shell, and waits for a systemd timer to execute it. Fifteen minutes later: root in the guest VM.

Is This a Guest-to-Host Escape? Understanding the Blast Radius

Let's be precise about the blast radius. This is a container-to-guest-VM escape, not a guest-to-host escape. The hypervisor boundary holds. The attacker gets root inside the microVM but cannot reach the host, cannot reach sibling VMs, and the overwritten content doesn't survive a reboot.

That's not nothing, though. In Kata's architecture, the guest VM runs kata-agent, which manages the container lifecycle. Root in the guest means control over the agent, which means influence over the pod. The isolation model held at the hypervisor layer but failed at the guest layer. The boundary that was supposed to be opaque turned out to be permeable.

The interesting question isn't "how bad is this CVE." It's "why did the architecture make this possible in the first place."

The Hidden Trust Assumption in MicroVM Architectures

When you DAX-map guest image content, you're making an implicit trust decision. You're saying: the guest kernel will correctly enforce access controls on this memory region. The hypervisor doesn't need to be in the critical path because the guest will do the right thing.

That's a reasonable performance optimization if the assumption holds. But the assumption is doing a lot of load-bearing work, and this CVE is what happens when one link in the chain fails to uphold its end.

This isn't unique to Kata or to pmem. It's a general pattern: any time you remove the hypervisor from the I/O path for performance, you're transferring a trust decision from a component you control to a component running inside the boundary you're trying to enforce. You're asking a wall to police itself.

Walls are bad at policing themselves.

How Edera’s Isolation Model Avoids Guest Trust Dependencies

We made a different decision. It wasn't an accident and it wasn't because we didn't know about pmem. We chose to keep the hypervisor in the I/O path for guest image content.

Edera serves guest images as squashfs on read-only block devices. It's simple, almost boring. Every I/O operation goes through the hypervisor, which means the hypervisor can reject (NAK) any write that shouldn't happen. The guest kernel's opinion about whether a region is writable doesn't matter, because the guest kernel isn't the one enforcing it.

We made the trade off with direct performance deliberately, because simplified models yield greater security, and we'd rather explain a rounding-error performance number than a CVE.

The same principle extends to how we handle the agent. Like Kata, Edera runs an agent inside the guest (protect-zone) that makes containers do container things. Unlike Kata, our host domain (dom0) doesn't trust it. The agent has scoped access to the control plane through an OCAP-like capability model. It can do what it needs to do and nothing more. Co-located processes can't observe it or interfere with it. If an attacker somehow compromised the agent, the damage would be bounded by the capabilities the agent was granted, not by whatever the attacker can reach from a root shell.

We treat domU as untrusted. Not because we think our agent code is bad, but because the moment you start trusting code running inside your isolation boundary, you've moved the security boundary to a place you can't enforce from the outside.

Trust or Verify? How to Evaluate MicroVM Isolation Architectures

This CVE will get patched. Kata 3.27.0 already addresses it. The project will be fine.

But the architectural question it surfaces is worth sitting with. Every microVM runtime makes trust decisions about the guest, what the guest kernel enforces, what the guest agent can access, how configuration and image content cross the boundary between host and VM. These decisions are often invisible. They look like performance optimizations or implementation details. They don't show up in feature matrices or comparison blog posts.

Until they show up in a CVE.

The question isn't whether you trust the guest today. It's whether your architecture requires you to trust the guest in order to maintain its security properties. If the answer is yes, you've built a system whose security depends on the correct behavior of the thing it's trying to contain. That's not isolation. That's a strongly worded comment in kernel source.

If you're evaluating microVM isolation: for containers, for AI agents, for multi-tenant infrastructure, ask this question. Look at where the hypervisor is in the I/O path. Look at what the guest agent can access. Look at what happens when a component inside the VM misbehaves.

The answer tells you more about the architecture than any feature comparison ever will.

FAQs

What is CVE-2026-24834 in Kata Containers?

CVE-2026-24834 is a 9.4 severity vulnerability allowing a container process to overwrite binaries inside a Kata microVM guest image using pmem and DAX, resulting in root access inside the guest VM.

Does CVE-2026-24834 allow guest-to-host escape?

No. The vulnerability enables container-to-guest escalation but does not cross the hypervisor boundary to the host or sibling VMs.

Why is trusting the guest kernel risky in microVM architectures?

When performance optimizations remove the hypervisor from the I/O path, security enforcement shifts to the guest kernel. If the guest misconfigures permissions or drivers, isolation guarantees weaken.

What should you evaluate in a microVM isolation model?

Examine where the hypervisor sits in the I/O path, what the guest agent can access, and whether security depends on correct guest behavior.

-3.png)